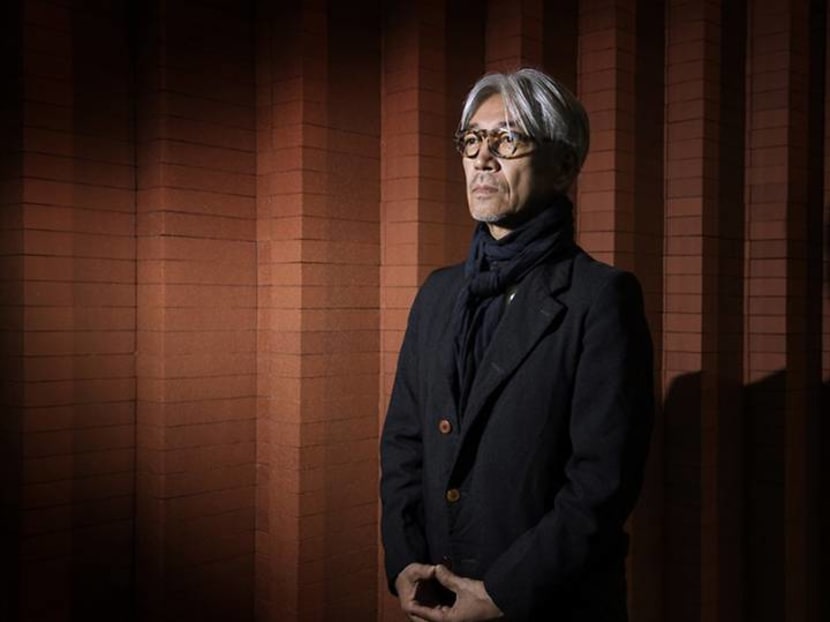

Award-winning composer Ryuichi Sakamoto: ‘True creativity is destructive’

Advertisement

People

Award-winning composer Ryuichi Sakamoto: 'True creativity is destructive'

Sakamoto reminisces near the artistic spirit of the 1980s, and bemoans the damage the pandemic has done to musicians and live music. But he likewise sees creative opportunity in the virus's shadow.

"To create something is a very foreign thing to do. Considering I want to create something new, it means I have to break what I have, break down what I think and what I would normally do," believes Ryuichi Sakamoto. (Photo: AFP/Joel Saget)

In a parallel universe, this paragraph would have been written in the JFK departures lounge with a bag of disappointing gifts at my feet, a xiv-60 minutes flight to Tokyo boarding any infinitesimal and a notebook still crackling with the previous day's electric discharges from Ryuichi Sakamoto.

I would have arrived early at Te Visitor in New York's West Village to handbag a table in a tea business firm described in The New Yorker every bit 1 of the metropolis's most thrilling places to eat: A fitting venue to interview a human being whose dandy contribution to the 1970s and 1980s was to evidence the globe via pioneering electronic popular that Japan was not just an epically ambitious industrial power but also a biggy hive of cool.

Sakamoto's power as a musician – the forcefulness that has blasted him betwixt early hip-hop and Olympic opening-ceremony anthems – has been the power to shift between influences, instruments and engineering science, managing with each movement to sally every bit the arch innovator.

Inevitably and immaculately the musician, songwriter, performer, producer and activist would, I imagine, take arrived 15 minutes earlier me. I would have found him in his favourite corner with a mug of oolong and, possibly, the start filaments of a new limerick meshing in his head. Droplets of tea steam would have condensed on his designer glasses. Te Company's peanuts with Sichuan peppercorns, braised pork and signature pineapple linzer would have far exceeded their reputation. The bill would not have troubled the FT expenses section. The flight to and from Nippon would have registered as perfectly ordinary business concern travel.

It would all accept been lovely. "Only plans," the existent-life, gently spoken Sakamoto declared, with the bittersweet tone of someone who had a brush with cancer just a few years ago, "no longer mean very much."

He is right. The globalised, mass theft of the world'southward plans – of everything from restaurant bookings to Glastonbury, geopolitical summits and the Tokyo Olympics – has been another dismal outcome of the COVID-nineteen crunch.

By the time Sakamoto and I meet virtually over Skype, the musical genius who wrote the haunting score for Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, is testify-stoppingly kissed by David Bowie in that movie, scored The Sheltering Heaven and won an Oscar for The Last Emperor has not taken a step outdoors for weeks.

He is self-quarantined in Manhattan, where he lives with his partner; I am in Tokyo, where Sakamoto was born, nether a state of emergency, and with a box of supermarket sushi on my desk-bound. Neither of usa is going anywhere. "And these," said the electronic maestro, raising a small-scale glass of orangish juice, a flask of water and a cup of coffee to his laptop camera, "are my lunch with the FT."

Sakamoto, who wears black and grayness and conducts our discussion as if he has just closed the door on some brilliant slice of mischief, nevertheless counts himself lucky. He bemoans the damage the pandemic has done to musicians and live music, and how it has culled the variety of roles that music plays in day-to-solar day life. Simply, an optimist, he sees creative opportunity in the virus's shadow.

"It is at times like these that the creators and musicians go more unique ideas than they do in normal times," he said, arguing that the brokenness of normal life is an unexpected fillip to a certain type of creative person.

"To create something is a very strange thing to practise. Because I want to create something new, it ways I have to break what I have, break down what I think and what I would normally do."

There are other spurs: Swain artists around the world have suggested projects to him under lockdown that might never have arisen otherwise, and the pandemic has spurred connections or reconnections that pre-pandemic schedules would have fabricated incommunicable.

"The reconnection . . . " he said, pausing for several seconds and visibly deciding against revealing that he might be working with a erstwhile collaborator, " . . . particularly in these times, it'southward very important."

And the truth, he confides, is that as a permanently decorated composer, he actually didn't get out all that much anyway. The fundamental shape of the Sakamoto 24-hour interval – what he calls the essential on-off switching between the part of the studio where he works and the role where he "freshens his brain" on the sofa – is only partially inverse.

As it turns out, he is in the studio while we are talking, but is reluctant to let it to be seen and has instead gear up a digital background to block information technology with a vista of New York'southward skyline. Sakamoto, for almost five decades a pioneer of synth-pop, electronica, ambient firm and cyberpunk, offers a traditional tatami room as an alternative background. Which nosotros make up one's mind feels incorrect.

'True CREATIVITY IS Subversive'

Throughout our chat, we bear on on the influence of moments of bully trauma, of which COVID-19 is merely the most recent. For many years, Sakamoto has lived primarily in New York and was there on September 11, 2001. For a long period after the attacks, he was quite unable to listen to whatever music. "I was too tense," he said.

A decade later on, on a visit to Tokyo, he experienced the same terror when the Tohoku quake and tsunami tore through Nippon's eastern coast, causing almost 20,000 deaths and triggering the Fukushima nuclear meltdown. It was the aftermath of the Fukushima accident in particular that pushed him to anti-nuclear activism – turning a widely beloved, avant-garde troubadour into a committed critic of the government and its industrial base.

And now, he says, COVID-19 is reviving that aforementioned suite of fears for a third time – a creeping sense of a crunch and a failed response. He wonders, for example, whether Nippon's reluctance to engage in broad-scale testing was an effort to downplay the early on weeks of the outbreak to preserve the Tokyo 2022 Olympics. And yet he knows, in his centre, that activism in Nippon is likewise often fruitless.

"This is the right time for the Japanese people to finally express their anger. There are so many people concerned nearly safety and security. And so many Japanese are anxious and aroused. But they won't practice it, unfortunately. The younger ones – they are really more conservative. It's very deplorable, actually," he said.

We linger on how Sakamoto, both cherished at home equally a national treasure only and then long an observer of Japan from afar, views sure cliches of the Japanese grapheme. We discuss, in particular, the notoriously punishing culture of long hours and overwork that pervades corporate Japan and which extends throughout the country's artistic industries. He vigorously agrees.

"About 35 years ago, I met the French composer Pierre Barouh. He told me at the time that he was going . . . to Brazil for 3 months to write lyrics," said Sakamoto, briefly unable to continue because he is laughing so hard, " . . . for just 3 or 4 lines of lyrics. To Brazil! Information technology was so boggling to me. At the fourth dimension I was doing four to v sessions a day, jumping from one studio to some other and working from noon to midnight every day. I did that for three decades, and I merely stopped when I was diagnosed with [oropharyngeal] cancer a few years ago. The idea of going off somewhere for inspiration for a lyric was more than I could always dream of."

Sakamoto is still both amused and worked upward when I inquire him about monozukuri. The term, which literally translates equally "matter-making", is used to ascribe a shared Dna to a Sony Walkman, a Toyota selection-up truck and a lacquerware jewellery box, and is often touted as the pre-eminent quality of Japanese-ness. I inquire whether his composition of music – so widely varied and notwithstanding and then distinctively of Sakamoto – could be described as monozukuri.

He hates the word, and his irritation is revealing. "True creativity is destructive," he said, taking a deep, ranty breath. "You have to break things to make something new. Monozukuri is just polishing existing thinking. True creativity is making something entirely new. Something revolutionary and something destructive."

He illustrates his point by recalling his first e'er walk down the King'southward Road in London, at some fourth dimension in the early 1980s. Sakamoto leans closer to the laptop camera – faintly conspiratorial but briefly causing his confront to fishbowl across my screen. Information technology is the merely moment, during the tiffin, in which he is anything other than absolutely poised.

During his stroll, Sakamoto encountered a young skinhead whom he reckoned was about nine years old. "He was so wild. Weird eyes, smoking a cigarette. It was and so inspiring. Shocking, but I really liked information technology. I'd only never seen a child like that in Japan. The manner, the expression and the mental attitude were different: It was a positive culture shock. I felt the same scent and texture of violence in the music, and I loved it."

"Truthful inventiveness is subversive. Yous take to break things to make something new." – Ryuichi Sakamoto

REMINISCING ABOUT THE 1980S

Yet there are many who say that Sakamoto – particularly the generation that remembers him as the co-founder of Yellow Magic Orchestra and for songs such as Anarchism in Lagos – was also identifiably the essence of a item fourth dimension in Japan.

In preparation for my virtual lunch, I accept spent hours trawling YouTube for live performances of his concerts in the 1980s – performances where the aesthetics, vibrancy and the sounds of Sakamoto and his entourage felt similar perfect symbols of Nippon in its high-growth, bubble phase.

In recent years, he admits, he has tried to distance himself from that phase of his career – more often than not, one feels, to avert having to perform and re-perform his best-loved music to endlessly ravenous audiences.

Just I accept touched a soft spot. In their mad backlog and almost self-witting strangeness, the 1980s in Nippon, admits Sakamoto, were hugely enjoyable. "Around that fourth dimension, Tokyo was the nearly interesting city in the entire earth. Mode. Music. A lot of strange stuff. Sometimes I am nostalgic for then. Sometimes," he said.

It was, he adds, only office of a wheel. At any given time, he argues, some city in the globe is at the epicentre of everything – the generator of creative waves that crash effectually the globe but at the same time suck in the greatest talent. But then the cycle moves on. New York, London, Tokyo, Paris – they have all had their moments. "Always strange artistic people get together in the middle of coin," he concluded, catastrophe the thought on an uncharacteristically mercenary note.

In add-on to his work with YMO, Sakamoto has a long career producing music for films – a four-decade run of composition that has netted him an Oscar, Bafta, Grammy, Gilt Globes and other trophies, but likewise includes work on some fabulously ropey lower-budget Japanese productions.

One of these was the notorious 1991 film Tokyo Decadence, an erotic thriller well-nigh an abused prostitute that was so stunningly depraved it was banned in several countries. I mention to him that the opening credits – played to a haunting Sakamoto score that wildly outclasses the film – were shot along my usual route between habitation and the FT office. The film, nosotros agree, is some distance from more recent piece of work, which includes the 2022 Oscar-winner The Revenant.

The shift was a witting one. Earlier in his career, he says, a younger and more than selfish Sakamoto wrote motion-picture show music for himself. He didn't care about the films, and so information technology didn't matter if they were terrible. In fact, the worse they were, the more his name would stand up out, which he used as an incentive to write superb music.

"But nigh ten-xv years ago my ideas changed 180 degrees. At present I do intendance about the motion picture more than my own scores. I desire to devote myself and my music to making the picture better. So for case with The Revenant I don't want my music everywhere. I want it subconscious in among the voices and the texture of the film," he said, while noting that he is less interested in recreating the kind of anthemic theme tunes of Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence. "Younger directors offer me to write something similar that. I tin can do that at present simply information technology's not actually my intention to make this very huge dramatic music."

A few minutes after, as we are nearing the end of our meal, something unexpected happens. He sings. Well, hums. The chat, without either of us exactly knowing why, has tumbled upon what is arguably his greatest popular composition – the 1978 song Behind the Mask, which feels as if it was made for the COVID-19 era. The song, which Sakamoto originally sang in English, was successful in Nihon and fifty-fifty more and so in the world beyond, eventually being covered by three western artists, including Eric Clapton.

The vocal famously caught the attention of Michael Jackson, who rewrote the lyrics and would, had at that place not been a rights dispute with YMO, take included the song on Thriller, the bestselling album of all time.

As we reminisce, Sakamoto hums a single bar of the instantly recognisable riff of Behind the Mask. "I don't know what exactly it was that drew western people to that vocal . . . some essence of rock 'n' roll, the harmony, phrase, tempo, some combination. It'southward completely extraordinary to me," he said.

And if it had made its mode on to the Thriller album? "It would have inverse my life. I would have retired at the historic period of 35 and be on a Greek island."

That didn't happen. So what is the current Sakamoto work? The question takes usa back from the zingy, COVID-xix-free 1980s to Manhattan and the globe under lockdown. His music volition focus on the concept of "incomplete" – an appropriate notion, he says, for a man who has come up shut to death and could face up it again at any time.

"It is music that is not finished. So incompleteness is for me finding something new all the fourth dimension and at every moment. And also we are in the time when we don't know where we are heading so the whole world is incomplete and our lives are incomplete. Mayhap it sounds Buddhist. I like the audio of it," he said, with that glint of mischief again.

"Nosotros are in [a] time when we don't know where we are heading so the whole globe is incomplete and our lives are incomplete. Maybe it sounds Buddhist. I like the sound of it." – Ryuichi Sakamoto

Past Leo Lewis © 2022 The Fiscal Times

READ> The artist who brought the sound of Singapore to the Venice Biennale

Recent Searches

Trending Topics

Source: https://cnalifestyle.channelnewsasia.com/people/award-winning-composer-ryuichi-sakamoto-247671

0 Response to "Award-winning composer Ryuichi Sakamoto: ‘True creativity is destructive’"

Postar um comentário